Don’t Give Pigweed The Light Of Day

For the last three years, the Beltwide has kicked off with the Consultants Conference, sponsored by Syngenta, Bayer CropScience and Dow AgroSciences. And as you might expect, a good portion was spent on weed resistance management.

Resistance to one herbicide or others across the Cotton Belt ranges from a high of 18 in California to none in Arizona. The Mid-South states average the highest.

The most troublesome weed by far is Palmer amaranth, followed by marestail.

Georgia Extension weed scientist Dr. Stanley Culpepper said he’s fought it long enough to realize that the best control of resistant Palmer amaranth is to keep it from ever germinating.

“If you have dryland production in the Southeast, Mid-South and the Mid-Atlantic states and think you can go in with 50-something-dollar herbicides and control resistant Palmer amaranth without rain, you will lose,” he said. “If we integrate them with programs that deep-turn the land, we can reduce the amount of Palmer amaranth seed that emerges by 50%, and that greatly improves control. Conservation tillage growers can also do that by using a rye cover crop to reduce emergence.

“The goal is, if it doesn’t come up, you don’t have to kill it.”

Culpepper said when cover crops and deep tillage have been used together, resistant Palmer amaranth control has been improved by 90% in Roundup Ready programs.

In the Mid-South, burndown is still a common practice.

“Traditionally, three herbicides have been used for burndown ― Gramoxone, glyphosate and, in some cases, 2,4-D,” said Dr. Larry Steckle, Extension weed specialist at the University of Tennessee. “In the late 80s and early 90s, there was still a fair amount of Gramoxone and Roundup being used, but they were both pretty pricey at the time. That changed when Roundup prices started to come down.”

Steckle said in parts of Louisiana, there were pockets where 2,4-D continued to be used, but that didn’t happen in Tennessee and he began to see problems with marestail where Roundup alone was used.

“That worked pretty well until about 2003,” he said. “So we’re familiar with marestail now in Tennessee and most of the Mid-South. I don’t think they have it quite as bad in Louisiana, but it’s moved into the Southeast. It is the most wide-spread glyphosate-resistant weed, and was the first confirmed.”

But Steckle said you can’t place all of the blame for glyphosate resistance on row-crop agriculture.

“It didn’t happen in a vacuum,” he said. “What’s the number one product being used by highway departments or other people trying to control weeds on roadsides? It’s glyphosate. Look at railroad tracks, city streets and cracks in sidewalks.”

Steckle said he’s been shocked at how populations of marestail have exploded since 2001. In some cases populations have built to the point where it’s not unusual to find 30 to 40 plants per square foot ― “Like a carpet,” he said ― and controlling it is a challenge.

Unlike some annuals, marestail will germinate in Tennessee 10 months out of the year, beginning in the fall with another heavy flush coming in the spring ― mostly in April to early May.

Double Trouble

Steckle said we’ve now reached the point where we have to begin thinking in terms of controlling “resistant weeds” instead of “resistant marestail” or “resistant Palmer pigweed” because they are both beginning to show up in the same field.

“We have to manage them both,” he said. “There’s a new product from BASF called Sharpen that I’ve been looking at for five years and I’ve been very impressed with the marestail control. I still like dicamba, Roundup and Gramoxone.

“But if you have Palmer pigweed, too, then you’re going to have to overlap with residuals ― Cotoran, Caparol, Prowl ― to have any chance to do a good job of controlling them.”

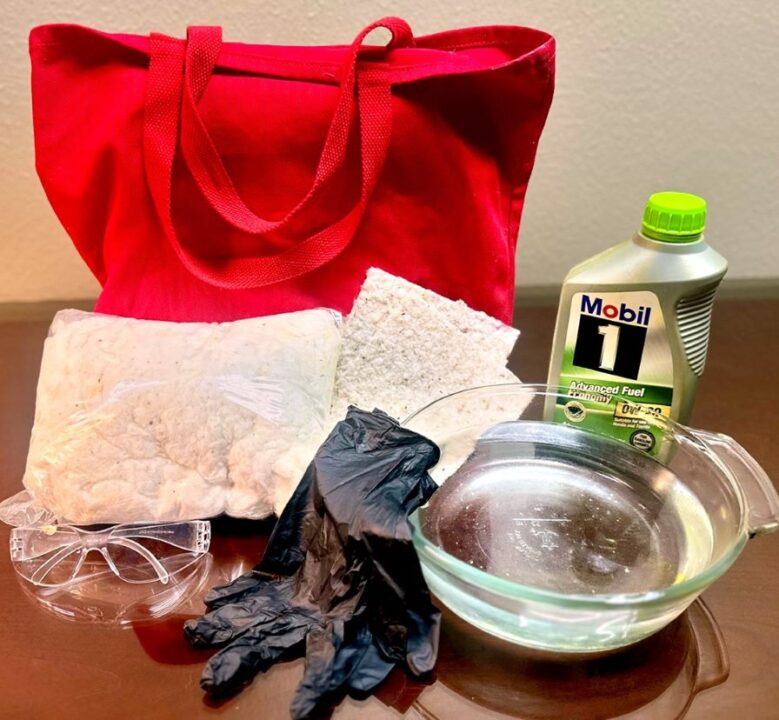

Add photo to side bar