Supply Will Hold Steady Despite Diminished Acreage

It’s been over 230 years since the “father of economics,” Adam Smith, said those words. In every respect, they have stood the test of time. But in the modern cotton market, as in other markets affected by recent scientific advancements and globalization, the concept of Smith’s ‘invisible hand’ seems to be coming into question.

Smith argued that businessmen, in our case cotton producers, would look out for what was best for them, and in doing so would achieve what was best for society. In large part, we have seen cotton growers doing just that of late.

As cotton draws lower prices on the global market, farmers worldwide have switched to other, more profitable crops. The ebb and flow of the market, as a result, will call for higher cotton prices as soon as demand catches back up with supply. But a kink has been thrown in the market’s own natural way of righting itself: technology happened.

In places like Brazil, the U.S. and China, vast amounts of acreage has been designated for other crops. Where endless rows of cotton once stood, there are now vast amounts of grain, corn, soybeans and other crops. Under normal conditions, excess cotton would be consumed and the natural fiber would again become more valuable. The looming problem with cotton, however, is that as acreage has gone increasingly down, yields and production have continued to increase.

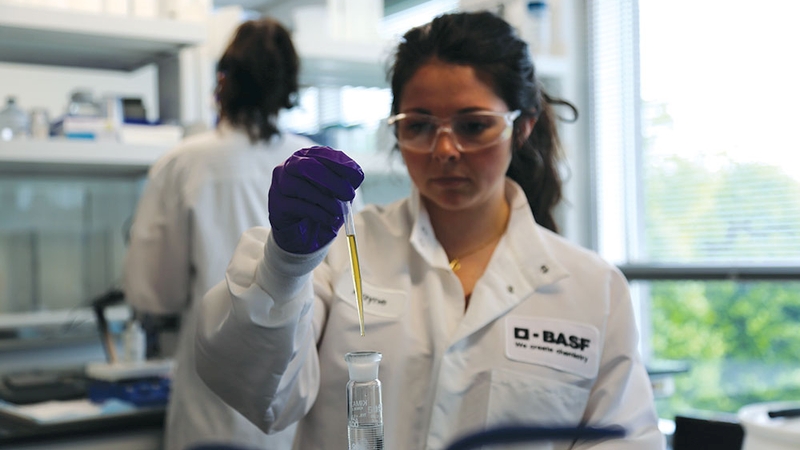

photo

In 1993, according to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), Brazil harvested around 1,085,000 hectares of cotton and produced just over 483,000 metric tons. Less than ten years later, in 2002, the country harvested only 735,000 hectares, but produced an eye-popping 846,956 metric tons of cotton. Similar trends can be seen world wide.

Based on the International Cotton Advisory’s bulletin Cotton: World Statistics, harvested area trended downward between 1997/98 and 2007/08 in North America, South America, French Africa, Western Europe and the Middle East. During the same time span, actual production trended upwards in each of those areas, except for French Africa. Advances in seed manipulation, soil treatment, pesticide and irrigation can account for the yield boom the cotton market has seen.

The problem for the market, then, is that production is holding relatively steady despite acreage being down. Instead of creating a demand for cotton by not planting it, growing methods have become so effective that they are inadvertently helping to maintain a flooded market.

If production continues in this fashion, despite attempts to stifle it, then the industry’s saving grace can only be a significant rise in demand. Cotton’s salvation lies in an environmentally aware consumer base, a general rise in global population, and a rising middle class – specifically in Asian markets. All three of these factors are very much a reality.

The boom in cotton yields isn’t the first time Smith’s theory has been tested in the free market, and it probably won’t be the last. But if the cotton industry hopes to right itself by driving up demand, it cannot rely solely on a decrease in production. Farmers worldwide have demonstrated that they will do what’s in their best interest by devoting land to alternate crops. But because of technology, supply will remain steady. Marketing, then, becomes the key to driving up cotton’s value.